|

Elena Terekhova

400 years of Belfast: the Abandoned Town [0] - 02.02.2025

No more ‘roast beef’ for a LinenopolisWhat’s the key to a miraculous change of Belfast of the 18th century into one of the most prosperous towns in Ireland? It’s linen production, mostly home-made and widespread. What served the impact to Belfast’s industrialization? Linen production did, namely when mechanization within the textile industry shifted it from the rural areas to towns. Why was Belfast vulnerable to the Great Famine of the 1840s? In a variety of factors one can definitely notice linen industry dependency upon the well-being of the workers which was ruined by the agricultural depression.

1842 Belfast as described by William Thackeray appeared "hearty, thriving and prosperous, as if it had money in its pocket and roast beef for dinner”. Who could foresee Belfast of 1845 then – the refuge for the poorest from around Ulster and Ireland, home for the linen industry workers living on the verge of poverty and starvation, battleground between different ethno-religious groups which got more polarized and conflict-prone? The Great Irish Famine affected county Antrim and Belfast as well as other towns and districts from South to North of Ireland.

‘The Great Famine’ Mural in Belfast expressing hunger during the famine. Belfast murals, mostly associated with the 20th century history of The Troubles of Ulster, are a distinctive city feature which has become a brand with more murals created after the decades of ‘political painting’. The murals of Belfast are often depicted on the gable ends of houses, being evolving in different ways: as true ‘survivors’ of the Troubles and as ‘heirs’ of pride in achievements, hopes and aspirations of Ulster people. Photo: Liz Droel © bordersoff

The causes of the Great Irish Famine, the measures taken by the British government and the final responsibility are often the subject of heated debate and criticism. The period was widely used in the nationalists’ rhetoric condemning all the measures of the British government as the ‘Catholics’ Genocide’, however one should bear in mind both Catholics and Protestants suffered during the Famine which mostly affected the poorest, like all famines.

The £5 of Hope

During the famine approximately 1mln people in Ireland died and a 1.5-2 mln more emigrated. This is when Belfast was in the limelight: a major port of departure to the New World and some other destinations, a shipbuilding town of aspirations and the great escape.

The voyage to the New World would cost £4-5 which was half an annual income of a factory worker. People were saving for years to emigrate, sometimes only the younger did, paid for by their relatives or charity organizations. The charitable bodies were many: Ladies’ Society for the Relief of Belfast Destitution, Belfast Ladies’ Clothing Society, Belfast General Relief Fund which established numerous soup kitchens around the town, Day and Night Asylum houses, supplied the poorest with clothing and blankets and provided medical help. By 1847, the second year of the Great Famine, the relief institutions were overcrowded and contagious diseases spread around, aggravated by the hunger.

Still some emigrants were lucky to obtain the tickets for crossing the Atlantics. The voyage was an ordeal with bad food and water, lack of space, hygiene and medicine to last for 4 to 12 weeks. As most of the emigrants were already too exhausted and often diseased, some of the ships became known as ‘coffin ships’.

But many were luckier. Upon arrival to a port of the New World all the emigrants had to pass medical inspection. It was feared by all, and the doctors used special signs to denote various types of illness or physical condition. ‘L’ meant lameness, ‘Pg’ – pregnancy, ‘X’ was for suspected mental illness. The sign feared most of all was ‘O’ crossed by ‘X’ in the centre signifying definite signs of mental illness and automatic deportation.

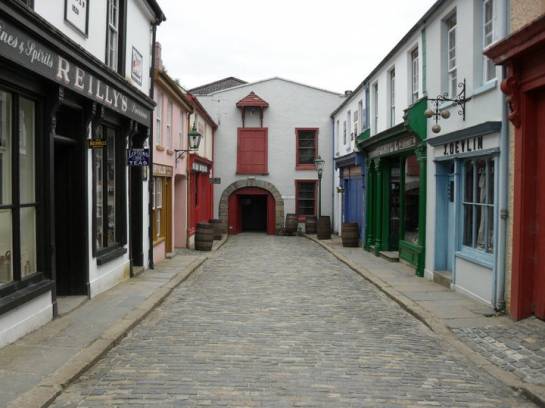

The best way to explore Irish emigration is to visit the Ulster American folk park, telling the story of migration in buildings, places, people, foods and ‘takeaway exhibits’. Situated in Castletown, Omagh, County Tyrone, it has many things Belfast, like buildings of old 19th century Ulster brought on the site from the streets of Belfast and a replica of an emigrants’ sailing ship Brig Union, built in Belfast. Photo: Carly Harte © bordersoff

Collect a ticket to the New World produced on an original 19th century press. Photo: Mirela Dimitriu © bordersoff

Have a look at the deck of the Brig Union (original-size replica), two-masted square-rigged sailing vessel, approximately 100 feet (30.5 metres) long. Photo: Raechel Wempen © bordersoff

Immerse yourself into the grim atmosphere of the ship’s interior: 200 steerage passengers squeezed together in the area of ‘tween-decks’, absence of ventilation and cooking facilities, creaking timbers, dirt and foul smells… But the permanent ‘several-weeks lodging’ would be soon changed onto the firm ground of Hope, ground of Life: Welcome to the New World! Photo: Raechel Wempen © bordersoff

Culture |29.01.2012 | Views: 1386

| Total comments: 0 | |